Chapter 4: Developing Effective Pricing Strategies

Why Pricing Strategies Matter for Every Health Economy Stakeholder

The healthcare cost curve has been “up and to the right” since World War II, and every American needs that to change. “You get what you pay for” is axiomatic except in healthcare, where almost no one understands what they bought, much less what it was worth.

Quality initiatives and the “triple aim” have failed to bend the cost curve meaningfully, if at all, because quality metrics are highly intangible. And, regrettably, the reversion to the mean in healthcare quality over the past 15 years has been to values that are stunningly average, as detailed in the Introduction.

Cost, on the other hand, is tangible, and health plan price transparency brings exactly that – transparency about what every provider was paid for the services the provider rendered at the location at which they rendered it.

In an era where everyone wants simple answers, health plan price transparency data provides one. Employers could bend the cost curve significantly merely by steering “away” from a handful of providers that are outliers on price or quality for a particular service line, in turn revealing the fallacy of “narrow networks” and steerage “to” a limited set of providers. Whether health plans and brokers fail to understand this or have instead chosen not to share this with employers is an interesting question.

The revelations from health plan price transparency data implicate the fiduciary duties of every corporate officer of every employer to evaluate potential cost savings from improved health benefit design. In turn, the potential of health plan price transparency to dismantle longstanding business models and financial arrangements necessitates every other health economy stakeholder to consider, perhaps for the first time, their pricing strategies.

For decades, pricing strategies in the health economy have had little effect because of information asymmetry between the providers of healthcare services – physicians, clinics, surgery centers and hospitals – and health insurers. Pursuant to the Sherman Act, the Federal government has not only endorsed but also enforced this pricing information asymmetry for decades. CMS’s Transparency in Coverage initiative changes all of that.

What Health Economy Stakeholders Are Doing Wrong, and Why

Every health economy stakeholder other than employers is guilty of ignoring the wisdom of the inimitable Peter Drucker, who described “The Five Deadly Business Sins” in an essay for The Wall Street Journal in October 1993:

- The first and easily the most common sin is the worship of high profit margins and of “premium pricing.”

- Closely related to this first sin is the second one: mispricing a new product by charging “what the market will bear.”

- The third deadly sin is cost-driven pricing.

- The fourth of the deadly business sins is slaughtering tomorrow’s opportunity on the altar of yesterday.

- The last of the deadly sins is feeding problems and starving opportunities.1

The U.S. health economy is without peer with respect to “cost-driven pricing,” which is deeply embedded into the status quo in both practice and mindset. A recent example of this mindset is a dispute between UnitedHealthcare and Mount Sinai Hospital (NY):

“Mount Sinai associate professor of OBGYN and senior medical director of Physician Contracting and Billing at Mount Sinai Health System, [sic] Dr. Alan Adler said the issue began after Mount Sinai learned UnitedHealthcare was paying less to them than other health care providers.

“We were able to see that we’re getting paid at least 30% less than the other academic centers. We still have the same labor costs,” Adler said.

UnitedHealthcare is accusing Mount Sinai of seeking a pay hike that would significantly increase costs. In a statement, a spokesperson said:

“Mount Sinai responded by repeating its outlandish demands that included two options — a three-year contract with a 43% price hike that would increase health care costs by $574 million — and a four-year proposal with a 58% rate increase that would increase health care costs by $927 million. All of Mount Sinai’s proposals would make its hospitals and physicians the most expensive by a considerable margin in New York City.”2

Putting aside the fact that Mt. Sinai’s in-network rates from UnitedHealthcare are higher than all but two academic medical centers in the New York CBSA and within 5-10% of the in-network rates of the second highest paid academic medical center, it is notable, if unsurprising, that neither party mentioned value, only relative reimbursement in the market.

There are two fundamental problems with this approach. First, neither party is focused on their customer, just their internecine squabble. Second, as Dr. Drucker noted:

“The worship of premium pricing always creates a market for the competitor. And high profit margins do not equal maximum profits. Total profit is profit margin multiplied by turnover. Maximum profit is thus obtained by the profit margin that yields the largest total profit flow, and that is usually the profit margin that produces optimum market standing.”1

Instead of trying to charge “what the market will bear,” Mt. Sinai should analyze its quality performance against the other academic medical centers in the New York CBSA to determine whether it is providing better value for money than its competitors. To the extent that it does, Mt. Sinai should use that to their advantage with the employers in the market.

As noted in Chapter 3, employers – the customer of every health economy stakeholder – have neglected their own financial interest in managing the cost of employee health benefits for decades. That, in turn, has catalyzed the proliferation of cost-driven pricing throughout the health economy.

The history of American business reveals many casualties of the “cost-driven pricing” mindset: textiles, steel, electronics, computer chips, etc. The existential question for every health economy stakeholder is whether they have the ability – and the courage – to adapt to “price-driven costing.”

Dr. Drucker summarizes the reason for “price-driven costing” this way:

“Customers do not see it as their job to ensure manufacturers a profit. The only sound way to price is to start out with what the market is willing to pay – and thus, it must be assumed, what the competition will charge and design to that price specification.”1

Logically, “price-driven costing” would force health economy stakeholders, especially healthcare providers, to adopt the principles outlined by Professor Regina Herzlinger in her 1996 book Market-Driven Healthcare: Who Wins, Who Loses in the Transformation of America’s Largest Service Industry. Instead of trying to be all things to all people, every healthcare stakeholder should consider the long-term prospects of every product or service they offer and exit those for which they cannot generate meaningful margin from being a market leader.

Similarly, Dr. Drucker reminds that the only way to deliver value for money is this:

“Activity-based costing provides the foundation for integrating into one analysis the several procedures required to create customer value. With activity costs as a starting point, the enterprise can separate activities that add value to customers from those that do not, and eliminate the latter. The chain of value-creating activities uncovered during value analysis is the starting point for analyzing the underlying process of value creation. Process analysis seeks to: improve the features of the product or service, restructure the process while reducing costs, and maintain or improve quality.”3

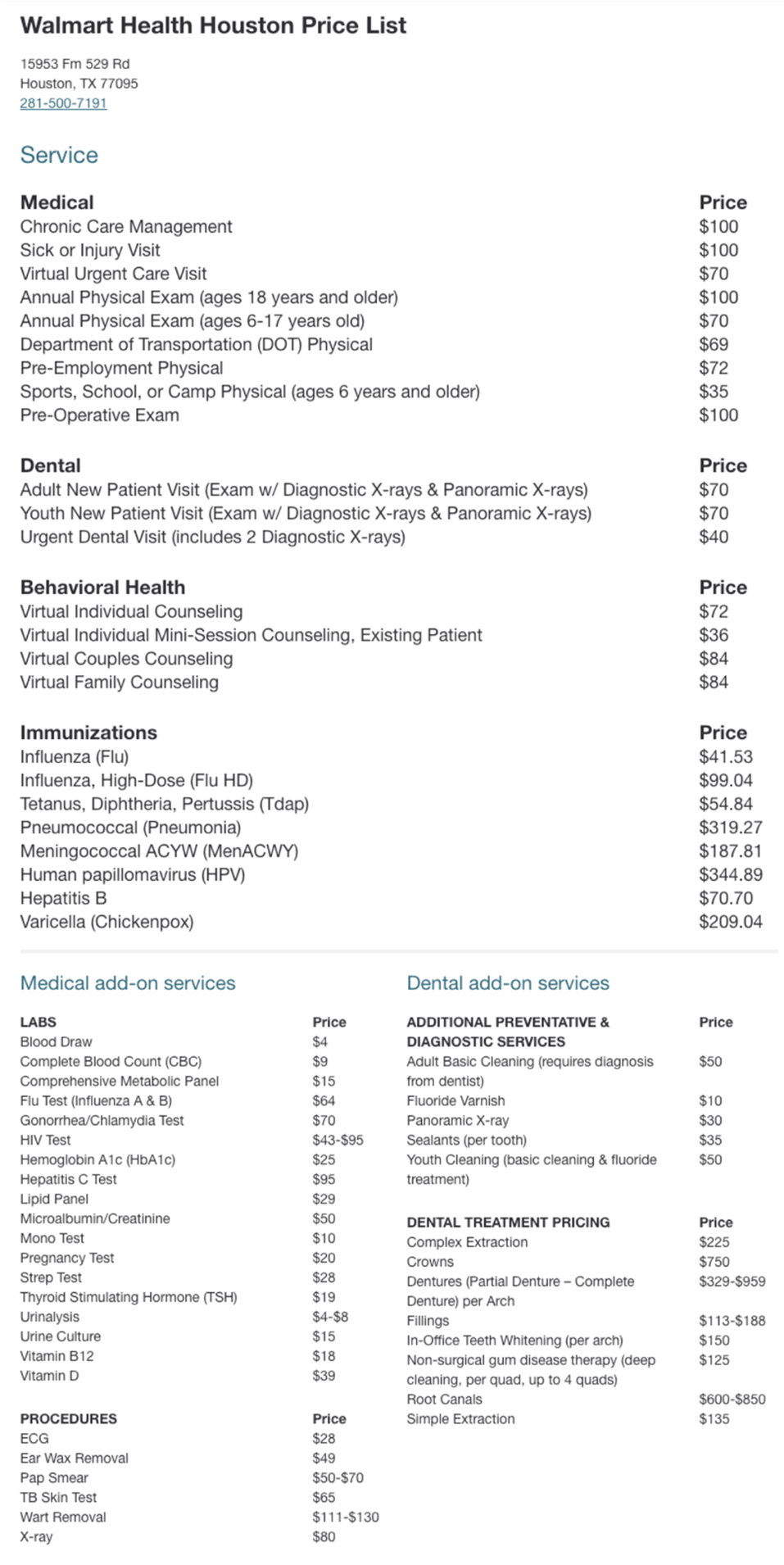

Traditional health economy stakeholders have never focused on delivering value for money, and those stakeholders should view the entrance of Amazon and Walmart into primary care as a portent. Amazon and Walmart have entirely different business models than traditional health economy stakeholders, through which they have developed the scale both to reduce their unit production costs and generate massive aggregate profits despite miniscule incremental margins. Said differently, Amazon and Walmart are playing a different game, one that other health economy stakeholders don’t understand and cannot execute successfully.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, as consumer-focused enterprises, neither Amazon nor Walmart needed the Federal government to mandate price transparency:4

Few health economy stakeholders can compete with Walmart’s prices, and none of them is as transparent. How long other health economy stakeholders can avoid competing on price is the most important question in the U.S. economy.

Why Value-Based Care Is Not – and Cannot Be – a Pricing Strategy

Given the Sherman Act’s longstanding prohibition on evidence-based pricing strategies, health economy stakeholders have instead focused on risk allocation strategies, especially since the implementation of the Medicare Modernization Act of 2003. The best known risk allocation strategy is “value-based care” (VBC) even though 15 years of CMS pilot programs have demonstrated no tangible evidence that VBC is consistently effective or scalable.

The industry’s zeal for VBC is curious since it is not designed to deliver value to the ultimate payer – typically the Federal government, a state Medicaid program or an employer – because VBC is focused on allocation of risk within a pool, not the reduction of the aggregate cost of the risk pool. Because in VBC the “true” payer is disintermediated from the entity providing the product or service, VBC can never be a pricing strategy. For these reasons and more, fee for service reimbursement remains the dominant payment model throughout the health economy.

Effective pricing strategy must be grounded in an understanding of negotiated rates for healthcare services and focused on delivering value for money to the ultimate payer for that product or service, aka the customer. In turn, producing value for money requires value-based competition by health economy stakeholders.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, several concepts promoted by stakeholders and consultants in the health economy are antithetical to creating value for money. The value of the narrow provider networks “created” by health insurers is generally limited to the network discount applicable to that narrow network, which incentivizes providers to raise prices simply to maintain current revenue levels, which incentivizes health insurers to demand a higher discount, a continuous game of Three-card Monte in which the employer is the mark.

Likewise, many “centers of excellence” are not, and obviously no single hospital or health system is the “best” in every single service line. It is self-evident that a “narrow network” designed around a single health system does not create value for money but instead inevitably sacrifices some aspect of quality at the altar of price. Similarly, any narrow network designed around inscrutable “quality outcomes” is incapable of creating the most value for money. Nothing, of course, is more antithetical to value for money than the clandestine rebates received by multiple health economy stakeholders from pharmacy benefit managers, except for cost-plus business models, the current “innovation” darling in Washington, D.C.

Why Health Plan Price Transparency Will Catalyze Novel Pricing Strategies

While CMS’s Transparency in Coverage initiative was intended to help consumers make more informed, price-conscious decisions, health plan price transparency is arguably more meaningful to employers, revealing the vast intra-market disparity in rates for identical health care services and providing pricing leverage they have never known they had. Price transparency leads to discovery of a “market price,” which leads to reduction in price spreads, forcing once-dominant business models and brands to adapt or go bankrupt.

The American Hospital Association was forced to use the Danish concrete case as the foundation of its opposition to price transparency because there are not any good examples in U.S. history of universal price increases following price transparency. In fact, the opposite usually happens. The deregulation of the airline industry paved the way for discount airlines like Southwest Airlines and businesses like Priceline and Kayak. Likewise, the development of the Internet browser allowed Kelley Blue Book to become the most visited automotive site on the Internet in 1995, radically changing the nature of automobile sales. More recently, the advent of trading stocks in decimals paved the way for E-Trade and Robinhood.

Price transparency has bipartisan support in Washington, D.C., and, in March 2024, several bills in Congress seek to codify and expand upon CMS’s Transparency in Coverage initiative. Providers that ignore the implications of price transparency are either naïve or foolish.

To date, most stakeholders’ curiosity about price transparency has been disappointingly sophomoric, focused on what other stakeholders are paying or getting paid. In fairness, the punishment for Sherman Act violations – a fine of up to $1M and a sentence of up to 10 years in Federal prison – has historically been a strong deterrent to price discovery. Health economy stakeholders must adapt to the radical new world of health plan price transparency in which employers can, and will, require providers and health insurers to defend their negotiated rates in every market for every product or service.

The Questions Every Stakeholder Should Answer

To develop effective pricing strategies, every health economy stakeholder must be able to answer:

- How do the stakeholder’s in-network rates compare to its competitors at the service-line level within each market?

- Are the stakeholder’s rates a market outlier?

- For providers:

- Are there service lines where the stakeholder provides above-average quality at a rate below the market median? Are there service lines where the stakeholder provides below-average quality at a rate above the market median?

- Are there service lines for which the stakeholder has comparatively high volumes and comparatively low rates? Are there service lines for which the stakeholder has comparatively low volumes and comparatively high rates?

- For payers:

- Which providers are being paid above-average rates by the stakeholder for below-average quality?

- Which providers are being paid below-average rates by the stakeholder for above-average quality?

- Are the stakeholder’s in-network rates correlated with the market share of providers in the market?

- For providers:

- What is the median market rate for the products and services (service lines, insurance products and services, medical devices, therapeutics) that the stakeholder offers? How large is the disparity in the rates that the stakeholder receives as compared to its competitors in the same market? What is the justification for the disparity, and is it sustainable?

- Can the stakeholder generate profit at that median market rate?

- How would a regression to the mean price in the market for the products and services (service lines, insurance products and services, medical devices, therapeutics) affect the stakeholder’s net revenue and profitability?

- How many products and services that the stakeholder offers reduce the total cost of care?

- How many products and services that the stakeholder offers are substitute goods for the products and services offered by its competitors? Are those products more expensive or less expensive than the substitute goods?

- For products and services whose value depends more on price and convenience than quality, how does psychographic data inform consumer preference for the products and services offered by the stakeholder?

- What does the current and future policy and payment landscape signal for the growth opportunities and constraints for the product and services (service lines, insurance products and services, medical devices, therapeutics) offered by the stakeholder?

Explore pricing strategies

Footnotes

-

https://ny1.com/nyc/all-boroughs/health/2024/03/02/some-unitedhealthcare-members-lose-mount-sinai-coverage ↩

-

Drucker, P, Management Challenges for the 21st Century, quoted from The Daily Drucker, page 207 ↩

-

https://www.walmarthealth.com/locations/tx/houston/1040/pricelist ↩